The history of the commercially recorded Bruckner Symphonies is peppered with instances where the true identity of the performers has been in question. The discography is filled with names such a Henri Adolf, Cesare Cantieri, Jan Tubbs, etc. who are conductors that no one has even seen. There are also recordings by such ensembles as the South German Philharmonic and the Hastings Symphony that have never given a public concert.

For this article, I am going to focus in on one recording of which it had been thought the true performers had been positively identified, but recent evidence seems to prove otherwise. The recording in question is the Allegro Royale LP No. 1597. The recording was released in 1954 and featured a performance of the Bruckner Symphony No. 3 as performed by Gerd Rubahn and the Berlin Symphony Orchestra. The Allegro Royale label was one of the first budget LP labels to reach the market after the advent of the LP. It was the creation of Eli Oberstein of the Record Corporation of America ("RCA") but not to be confused with the Radio Corporation of America, the real RCA. To keep the production price down, producers of this genre of LP resorted to low royalty recordings or used pseudonyms to cover up the real performers. Mr. Oberstein claimed to have a “Berlin source” for many of his productions. When this first LP of the Bruckner 3rd was released, there was a good deal of speculation regarding the real performers on this disc and there was one important clue - the performance on this LP used the newly published 1878 version of the 3rd Symphony as edited by Fritz Oeser.

In an article in the ARSC Journal, Ernst A. Lumpe continues the story:

Based on this article, the general conclusion was that the Allegro Royale was indeed a copy of the 1952 Leopold Ludwig performance with the Berlin Philharmonic.

In recent weeks, I attempted to provide more concrete evidence for this theory. Lumpe certainly had made a strong case for his identification, but the only way to be sure was to listen to the RIAS studio recording. Through the cooperation of Deutschlandradio (DLR) who maintains the RIAS archive, an audition copy of the March 6, 1952 studio recording in the Christuskirche, Berlin was made available in order to make the long-awaited comparison.

The results of this comparison indicated two important facts.

1) The LP record was indeed a concert performance. While the audience was well behaved, there are clear indications that an audience is present. The RIAS recording had no audience noise. There was not doubt that these were not recordings of the same performance. That finding coincided with Ernst Lumpe’s theory.

2) Further examination, however, indicated that the Allegro Royale recording was probably NOT by Ludwig and the BPO. While many elements of the two performances are similar, there are some distinct differences that would typically not show up in a recording made within the week of a concert. Timings alone show the wide variation:

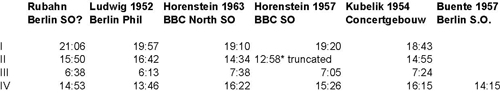

Allegro Royale: 21:06 15:50 6:38 14:53 Ludwig/BPO Studio: 19:53 16:42 6:13 13:46 Difference: + 1:09 - 0:52 + 0:25 + 1:07 With Ludwig / BPO now out of the running as the performers on the Allegro Royale LP, I began to look to other Oeser editions that were performed during this time. Comparisons were made with recordings by Jascha Horenstein (remembering Jack Diether’s earlier suggestion) Rafael Kubelik and Carl Buente, the conductor of the (West) Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. Below, is a table of timings:

Oeser Edition Performances of the Bruckner Symphony No. 3 - Timings

Based on these timings, there seemed to be little correlation between any of these performances and the Rubahn recording. The stylistic differences between Ludwig and Rubahn , apart from the timings, were too great. While the Buente timing was fairly close, only one movement was available for comparison and the 1957 performance was the conductor’s first performance of the symphony and was thus too late to be the source of the Allegro Royale recording.

Further, in recent e-mail communications with Misha Horenstein, the cousin of conductor Jascha Horenstein, it has become clear that Horenstein had not been introduced to the Oeser Edition until the BBC scheduled his performance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra on November 9th of 1957. And at that point, Horenstein had his doubts about the edition. He wrote to the BBC on October 25th, "I do not trust Oeser, and his edition is not convincing as far as I am concerned. I would prefer the “old” Rattig edition to the “new”Oeser-Edition, faute de mieux; still waiting for the final version. The fact that Oeser’s edition contains 100 bars more in the finale does not necessarily mean that Bruckner wanted them included. The bars missing in the Rattig edition could NOT have been excluded without Bruckner’s consent! Therefore I prefer an edition Bruckner has used himself, has known and accepted, Mahler has used for his piano score, to one of a Herr Oeser!" Eventually, the BBC recruited Robert Simpson to convince Horenstein to use the OeserEdition, but it is certain that Horenstein was not conducting the Oeser-Edition prior to the 1954 LP release.

Additional research has shown that several conductors were performing the Oeser-Edition in the 1960’s and could have performed it earlier. In addition to those mentioned above, they include: Klaus Bernbacher, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt, Lovro von Matacic and Harry Newstone.

In spite of the differences in timing, this author is beginning to lean towards the probability that Rafael Kubelik was the conductor. There are several stylistic similarities, most notably the use of extra percussion and the fact that Kubelik was actively touring with the symphony as early as January 28, 1954 when the performance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra was recorded.

So, as of this writing, the mystery still lingers an